Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

If you’re preparing for the Literature Drama And Poetry exam, this updated guide from EXAMRUNZ.COM will help you score high with verified questions and solved answers.

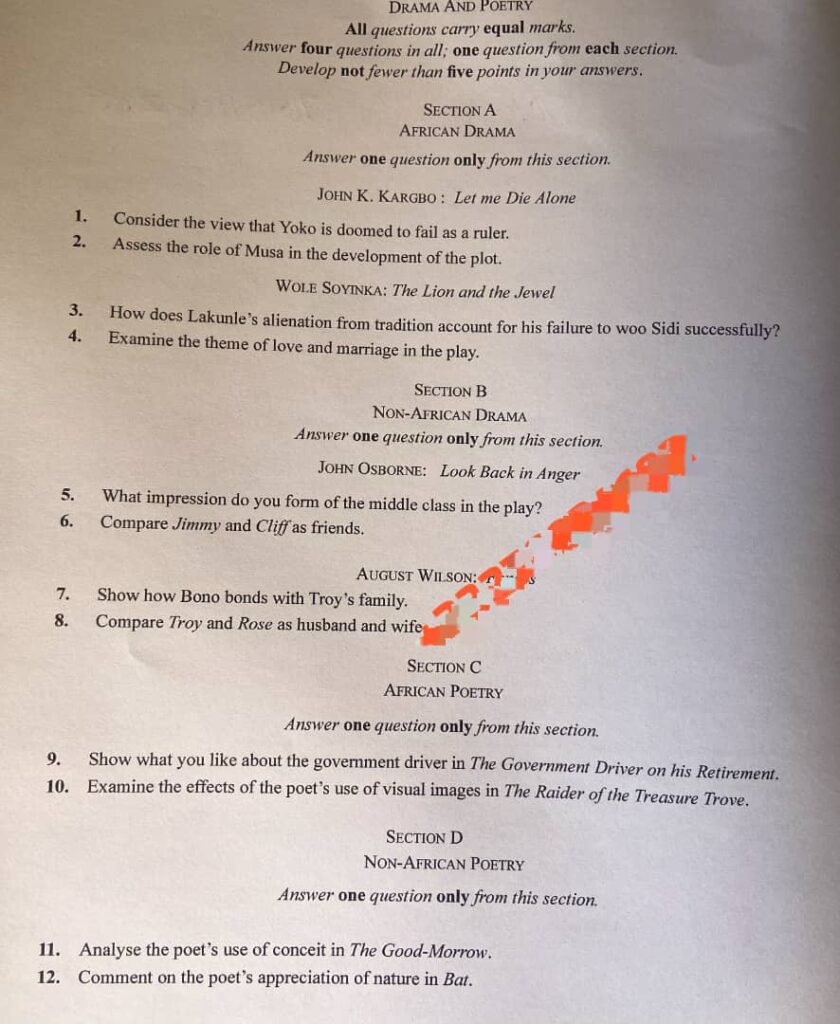

Thursday, 27th November, 2025

Literature-in-English 3 (Drama & Poetry) – 2hrs – 13:00 hrs – 15:00 hrs.

=================================

(1) Yoko’s downfall can be understood as the result of several forces that limit her authority and weaken her ability to rule effectively. First, her rise to power is shaped by patriarchal resistance. Although she inherits the throne, many male elders refuse to accept a woman as the supreme leader. This persistent opposition creates political tension and undermines her legitimacy. The playwright uses contrast and irony to show how her courage clashes with the narrow expectations of a male-dominated society, making her rule unstable from the beginning.

Her determination to uphold tradition also contributes to her failure. Yoko’s strict commitment to cultural obligations, including the ritual demands placed upon her, restricts her personal freedom and strategic choices. Her willingness to sacrifice her private desires to maintain the dignity of the chiefdom reveals her loyalty, yet it also exposes the rigidity of the system she protects. Through symbolism especially the rituals surrounding the throne, her position becomes a burden that steadily traps her rather than empowers her.

Another factor that shapes her doomed leadership is the manipulation she suffers from people within her court, particularly Musa. His cunning, deceit, and mastery of persuasive speech weaken her decision-making space. The use of dramatic irony highlights how Musa’s actions appear loyal on the surface while he quietly engineers situations that leave Yoko isolated. Her trust in him, combined with his hidden motives, creates internal instability and accelerates her loss of control.

Finally, Yoko’s emotional vulnerability deepens the sense of inevitable failure. Her struggle to balance compassion with authority leads her to make decisions that expose her to betrayal. The tension between her humane qualities and the harsh demands of leadership is shown through conflict and foreshadowing, which suggest that the pressures surrounding her role will eventually overwhelm her. In the end, her tragic choice to sacrifice herself becomes the final proof that the combined weight of tradition, manipulation, and gender-based opposition has left her with no viable path to succeed as a ruler.

============================================

(2)

Musa plays a central role in driving the tension of the storyline. His actions introduce conflict early in the plot because he constantly twists information for his personal benefit. Through his craftiness and selective storytelling, he creates misunderstandings that push other characters into emotional and political struggle. His use of deceptive speech functions as a dramatic device that heightens suspense and keeps the events shifting in unpredictable directions.

Musa also serves as a key agent of betrayal, which deepens the tragic movement of the story. His pretended loyalty to Yoko hides a deeper self-interest that guides many of his decisions. This double-faced nature creates dramatic irony, since his outward respect contrasts sharply with his internal motives. His betrayal weakens Yoko’s authority and contributes to the gradual erosion of confidence within the chiefdom. His behaviour exposes the fragility of power when surrounded by untrustworthy advisers.

Furthermore, Musa helps reveal the theme of manipulation in leadership. Through his continuous scheming, the audience sees how political ambition among close officials can shape the fate of a ruler. His actions push the plot from stability into growing chaos, showing how a single influential figure can redirect the course of leadership. His clever manipulation serves as a structural device that links several major events, making him one of the chief forces that move the narrative forward.

Musa also contributes to the tragic end of Yoko’s story. His influence feeds the pressure that surrounds her, leaving her emotionally strained and politically insecure. The distrust he cultivates and the misinformation he spreads help prepare the ground for Yoko’s final decision, making him a vital channel through which the play’s tragic resolution is achieved. Through his cunning, deception, and strategic influence, Musa becomes a driving engine of the plot and a major architect of the tensions that shape the entire narrative.

============================================

(3)

Lakunle’s failure to win Sidi comes mainly from the way his ideas place him outside the values of his own community. His rejection of traditional practices, especially the bride price, immediately creates a barrier between him and Sidi. She interprets his refusal not as progress but as disrespect toward her worth as a woman in the custom of Ilujinle. This clash of values sets the foundation for her resistance, and Soyinka uses contrast to show the wide gap between Lakunle’s modern ideals and the cultural expectations that define relationships in the village.

His language and behaviour further deepen this alienation. Lakunle constantly dismisses the community’s customs as “backward,” believing that Western ideas are superior. This habit of belittling the traditions that shape Sidi’s identity makes him appear arrogant and insensitive. Through satire, the play highlights how his imitation of foreign ways lacks genuine understanding, making him seem foolish rather than impressive. His inability to communicate respect weakens his romantic efforts and distances Sidi emotionally.

Another source of his failure is his misunderstanding of courtship within his culture. He approaches love with theories and speeches rather than actions that speak to Sidi’s lived reality. While he talks at length about modern marriage, he shows no awareness of how affection is demonstrated in the community. This dramatic contrast between his theoretical love and Baroka’s practical understanding of desire allows Baroka to win Sidi’s interest easily. Lakunle’s rigid idealism becomes a structural obstacle that prevents him from connecting with her.

Finally, Lakunle’s alienation blinds him to the symbolic value of tradition in shaping identity. Sidi takes pride in her beauty, her culture, and the honour attached to them. Lakunle’s attempts to change her before even winning her heart make him appear controlling. Soyinka uses irony to reveal that the very ideas Lakunle believes will elevate Sidi are the same ideas that push her toward Baroka instead. His separation from tradition ultimately leaves him without influence, causing him to lose Sidi to someone who understands and respects the world she belongs to.

===========================

(4)

Wole Soyinka’s “The Lion and the Jewel” presents a multifaceted exploration of love and marriage, deeply embedded within the context of cultural transition and the clash between tradition and modernity in a rural Nigerian village. The play doesn’t offer a singular, idealized view of either concept but rather dissects them through the perspectives of its key characters: Sidi, Lakunle, and Baroka.

Lakunle, the schoolteacher, embodies a Westernized, progressive viewpoint. His concept of love is intertwined with notions of romanticism and intellectual companionship, advocating for a marriage devoid of bride price a custom he deems barbaric and outdated. He articulates his affection for Sidi through verbose declarations and promises of a modern, egalitarian partnership. However, his actions often contradict his words; his reluctance to pay the bride price reveals a superficial understanding of the cultural significance of marriage within the community and hints at a certain level of self-serving idealism.

In contrast, Baroka, the Bale (chief) of Ilujinle, represents the embodiment of traditional power and cunning. His approach to love and marriage is pragmatic and strategic. He views Sidi not just as a potential wife but as a symbol of the village’s pride and a means to reaffirm his virility and influence in the face of encroaching modernity. His pursuit of Sidi is less about romantic love and more about asserting his dominance and preserving the traditional social order. Baroka understands the intrinsic value of tradition and leverages it to his advantage, presenting a stark contrast to Lakunle’s detached intellectualism.

Sidi, caught between these two opposing forces, initially appears as a naive village belle, flattered by both Lakunle’s flowery language and the attention of the powerful Baroka. However, as the play progresses, she demonstrates a shrewd understanding of her own agency and the power dynamics at play. Her eventual decision to marry Baroka is not simply a capitulation to tradition but a calculated move. She recognizes the limitations of Lakunle’s idealism and understands that true power and influence reside within the traditional structures represented by Baroka. Her choice can be interpreted as a strategic maneuver to secure her future and potentially influence the direction of the village from within.

Soyinka masterfully uses the characters’ differing perspectives on love and marriage to highlight the complexities of cultural change. The play doesn’t necessarily endorse one view over another but rather presents a nuanced examination of the competing values and priorities at stake. The theme of love is intricately woven with the theme of power, and marriage becomes a battleground where tradition and modernity, idealism and pragmatism, collide. The audience is left to ponder the true meaning of love and the role of marriage in a society grappling with its identity in a rapidly changing world. The play encourages critical thinking about the agency of women within patriarchal structures and the enduring power of tradition in the face of modernization.

=======================================

(6)

The friendship between Jimmy Porter and Cliff Lewis in “Look Back in Anger” is a complex and multifaceted relationship, characterized by both genuine affection and underlying tensions. While they share a close bond and provide each other with a degree of support, their friendship is also marked by significant differences in personality, social background, and life aspirations.

One of the key similarities between Jimmy and Cliff is their shared sense of alienation and dissatisfaction with the status quo. Both men feel like outsiders in a society that they perceive as being stifling and oppressive. Jimmy, with his fiery intellect and rebellious spirit, is particularly vocal in his criticism of the establishment, while Cliff, in his more understated way, shares Jimmy’s sense of unease and discontent. This shared sense of alienation forms the basis of their bond and provides them with a sense of mutual understanding.

They also share a close physical intimacy, often engaging in playful wrestling matches and sharing a bed in the cramped attic apartment. This physical closeness suggests a deep level of comfort and trust between the two men. However, it also hints at a certain level of emotional dependence, particularly on Cliff’s part.

Despite these similarities, there are also significant differences between Jimmy and Cliff. Jimmy is far more intelligent and articulate than Cliff, and he often uses his intellectual superiority to belittle and humiliate his friend. Cliff, on the other hand, is more easygoing and less confrontational than Jimmy. He serves as a buffer between Jimmy and the outside world, often defusing tense situations and providing a calming presence.

Their social backgrounds also differ significantly. Jimmy comes from a working-class background and has had to struggle to achieve his education and social status. Cliff, on the other hand, is from a more stable and conventional background. This difference in social background contributes to the underlying tensions in their relationship, as Jimmy often resents Cliff’s relative ease and comfort.

Ultimately, the friendship between Jimmy and Cliff is a complex and ambiguous one. While they share a genuine affection for each other, their relationship is also marked by power imbalances, social tensions, and differing life aspirations. Cliff’s departure at the end of the play underscores the fragility of their bond and suggests that their friendship may not be able to withstand the pressures of time and circumstance. Their friendship serves as a microcosm of the broader social and political tensions that are explored in the play, highlighting the challenges of forging meaningful connections in a society that is deeply divided by class and ideology.

==============================

(8)

Troy and Rose exemplify complex conjugal dynamics that combine deep affection, conflicting ambitions, and moral tension. As a husband and wife, they reflect the complexities of partnership: mutual care, compromised ideals, uneven power dynamics, and divergent responses to scarcity and betrayal.

On the level of affection, Troy and Rose display genuine care rooted in shared history. Rose’s devotion is often the emotional center of the household: she manages the domestic sphere, nurtures the children, and provides stability. Troy, for his part, offers protection and provision, even when provision is imperfect. Their interaction includes tenderness, humor, and an old familiarity that suggests intimacy built over decades. This emotional grounding explains why neither abandons the relationship lightly; their marriage is more than contractual — it is an emotional ecosystem.

Yet, their marriage is strained by conflicting values and repeated betrayals. Troy is often characterized by a stubborn self-regard and an inability to accept responsibility fully. His relationship with other women or with past traumas introduces rupture. Rose, expecting fidelity and partnership, experiences these ruptures as profound betrayals. Her response is not merely moral condemnation but a practical redefinition of herself: she acknowledges the damage, sets boundaries, and sometimes reorients her identity away from romantic dreams toward personal agency. The tension between Troy’s insistence on patriarchal authority and Rose’s moral insistence on family responsibilities creates sustained dramatic conflict.

Power relations in their marriage are asymmetrical. Troy often exercises decision-making power, influenced by patriarchal norms and his own self-image as provider. Rose, constrained by economic and social structures, exerts influence through moral suasion and domestic labor rather than overt authority. However, Rose’s moral capital — the ability to expose Troy’s contradictions and to claim the moral high ground — gives her a subtler form of power. The play illustrates how power in marriage can be both coercive and normative: Troy’s control is immediate, Rose’s control is enduring.

Economically, their marriage is shaped by scarcity and the pressures of survival. Troy’s job, disappointments, and the society’s racial limitations produce frustration and bitterness that seep into the marriage. Rose channels her energies into practical stewardship — stretching resources, caring for children — while Troy’s resentments sometimes misdirect into controlling behaviors. The economic dimension shows how external structures shape intimate relations, making personal failings also structural critiques.

Finally, their marriage evolves. Rose is not a passive victim; she adapts, claims dignity, and in some interpretations, achieves moral victory by refusing to be defined by Troy’s failures. Troy’s tragic dimension is that his strengths (pride, stubbornness) also become his undoing, and Rose’s moral resilience becomes the play’s ethical center. The depiction resists simple moralization: both are flawed, both have moments of nobility. The play uses their marital dynamic to explore larger themes: responsibility, betrayal, resilience, and the strains placed on love by social injustice.

=======================================

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

(10)

In Norman Nicholson’s “The Raider of the Treasure Trove,” the poet masterfully employs visual imagery to create a vivid and unsettling portrayal of nature’s destructive power. The poem’s impact is largely derived from its ability to evoke a strong sense of place and to immerse the reader in the scene of a coastal landscape being ravaged by the sea. The visual images are not merely decorative; they are integral to the poem’s exploration of themes such as the transience of human endeavors, the relentless force of nature, and the precariousness of existence.

One of the primary effects of the visual imagery is to create a sense of immediacy and realism. Nicholson uses concrete details to paint a picture of the coastal environment, describing the “gulls screaming,” the “sea gnawing,” and the “sand spilling.” These sensory details bring the scene to life, allowing the reader to visualize the landscape and to feel the force of the elements. The use of active verbs, such as “gnawing” and “spilling,” further enhances the sense of movement and destruction.

The visual images also serve to emphasize the contrast between the human world and the natural world. The “treasure trove” represents human ambition and the desire for material wealth, while the “raider” the sea symbolizes the untamed power of nature. The poem’s imagery highlights the vulnerability of human creations in the face of natural forces. The visual of the sea relentlessly attacking the land underscores the futility of trying to impose order on the chaotic forces of nature.

Furthermore, the visual imagery contributes to the poem’s unsettling and even apocalyptic tone. The images of destruction and decay evoke a sense of impending doom, suggesting that all human endeavors are ultimately destined to be consumed by time and nature. The “bones” and “wreckage” scattered along the shore serve as reminders of mortality and the impermanence of earthly possessions. The visual imagery creates a sense of unease and prompts reflection on the fragility of human existence.

The poet also uses visual imagery to create a sense of scale and perspective. By contrasting the smallness of the “treasure trove” with the vastness of the sea, Nicholson emphasizes the insignificance of human concerns in the face of the natural world. The imagery invites the reader to consider their place within the larger context of the universe and to recognize the limitations of human power.

In conclusion, the visual imagery in “The Raider of the Treasure Trove” is essential to the poem’s overall effect. It creates a vivid and unsettling portrayal of nature’s destructive power, emphasizes the contrast between the human and natural worlds, contributes to the poem’s apocalyptic tone, and invites reflection on the transience of human endeavors. Through his skillful use of visual imagery, Nicholson transforms a simple description of a coastal landscape into a profound meditation on the forces that shape our existence.

===================================

(11)

John Donne’s “The Good-Morrow” is a quintessential example of metaphysical poetry, characterized by its intellectual complexity, paradoxical arguments, and, most notably, its elaborate use of conceit. The central conceit of the poem revolves around the idea that the lovers’ awakening to their love is akin to a spiritual or even cosmic revelation, rendering all previous experiences and worldly concerns insignificant. Donne employs this conceit to elevate the experience of earthly love to a level of profound significance, rivaling religious or philosophical enlightenment.

The poem opens with a rhetorical question, immediately drawing the reader into the speaker’s introspective musings: “I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I / Did, till we loved?” This sets the stage for the speaker’s subsequent assertion that their past lives were merely childish pursuits, akin to being “weaned” or engaging in “country pleasures.” This initial comparison establishes the conceit by suggesting that their love has ushered them into a new, more mature, and fulfilling existence.

The most striking element of the conceit lies in the extended metaphor of the two hemispheres. The speaker declares, “Let sea discoverers to new worlds have gone, / Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown, / Let us possess one world, each hath one, and is one.” Here, Donne uses the geographical discoveries of his time to illustrate the self-sufficiency and completeness of their love. Each lover constitutes a “world” unto themselves, and together they form a unified, perfect whole, rendering the external world and its explorations irrelevant. This bold comparison elevates their love to a cosmic scale, suggesting that it encompasses all that is necessary for a fulfilling existence.

Furthermore, Donne reinforces the conceit through the imagery of the two “hemispheres” without “sharp north, nor declining west.” This implies that their love transcends the imperfections and limitations of the physical world. The absence of a “declining west” suggests that their love is eternal and unchanging, free from the decay and mortality that characterize earthly existence. The absence of a “sharp north” could be interpreted as a lack of conflict or negativity within their relationship, further emphasizing its idyllic and perfect nature.

The final stanza solidifies the conceit by asserting that their love is so pure and balanced that it cannot die: “If our two loves be one, or, thou and I / Love so alike, that none do slacken, none can die.” This echoes the earlier imagery of the two hemispheres, suggesting that their love is a perfectly integrated whole, incapable of dissolution. The conceit, therefore, serves to not only elevate the experience of love but also to explore profound philosophical questions about the nature of reality, the relationship between the individual and the cosmos, and the potential for human connection to transcend the limitations of earthly existence. Through this intricate and intellectually stimulating conceit, Donne transforms a seemingly simple love poem into a complex meditation on the power of human connection and its capacity to reveal deeper truths about the world.

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

Authentic 2025 Waec Gce Lit Drama And Poetry Answers

1 Trackback / Pingback